Madrid’s “Central Attack” in Transnational Trademark Law: Practice, Procedures and Considerations

by Bela Kelbecheva (L.L.M. 2019)

Despite obvious benefits of the Madrid system in Trademark law, the threat of a central attack—a Madrid peculiarity not found in other intellectual property filing systems—can dissuade practitioners and trademark owners from using it.[1] However, central attacks on basic marks within the five-year dependency period[2] are actually quite rare. With data gathered from the last decade, the World Intellectual Property (WIPO) and the International Association for the Protection of Intellectual Property’s (AIPPI) working groups have reported very few occurrences of successful central attacks on basic marks, with the bulk of such attacks occurring in the EU. With these statistics in mind, there are myriad procedural and strategic considerations a trademark practitioner should know when attempting to carry out or defend from a central attack: namely, that any invalidation proceedings on the basic mark started before the five-year dependency period’s expiration date, if successful, will have a partial or whole effect on the international registration. Furthermore, the ensuing transformation of the cancelled international registration into multiple national or regional applications (in the same territories as the ones designated in the international application) is only possible within three months of the official notification of cancellation by the International Bureau. In addition, these transformations will be subject to the various requirements of the national or regional Offices, but will benefit from the same date of priority as the cancelled international registration.

The Madrid system is comprised of the Madrid Agreement and the Madrid Protocol. The Madrid Agreement has 55 contracting parties: most countries of the European Union (‘EU’) joined in its early days, while China joined in 1989. The United States (‘U.S.’), however, is not a member. The Agreement set up broad principles for cooperation between Member States for the international registration of trademarks using the priority date of the national mark, under the supervision and centralized filing system of the World Intellectual Property Organization’s (‘WIPO’) International Bureau. According to U.S. trademark practitioners, the country did not originally join the Madrid system in part because of a provision in Article 6 of the Madrid Agreement that created a dependency period of five years between the national mark and the international registration. In the case of a cancellation initiated by a third party, in whole or in part of the national mark on which the international registration is based, the latter will be cancelled as well, affecting all subsequent international registrations in other Member States[3] – the so-called “central attack.”[4] The central attack includes cancellation proceedings which begin during the dependency period but do not conclude until after this period ends.

The Madrid Protocol (established in 1989) remedied this issue. Article 9quinquies of the Protocol provides a solution to the central attack, namely if the national mark is invalidated within the dependency period, the owner of the international registration has the possibility to transform the international registrations in other Madrid Member States into national or regional applications.[5] However, this transformation must be done within three months of the national mark’s cancellation (also referred to as the ‘basic mark’), and must cover the same goods and services as the original international registration. While the initial framework of dependency largely remains the same, Article 6 of the Protocol adds some clarification as to the cancellation of the national mark,[6] notably by providing a list of all possible cancellation actions that could be used to invalidate the mark within the dependency period. Finally, Article 9sexies of the Protocol establishes the supremacy of the Protocol over the Agreement where a country is a Member to both.[7] However, if seeking protection in a country that is only Member to the Agreement, and not the Protocol, one may not “transform” a basic mark into national or regional applications there following a successful central attack. Thus, damage control is more difficult in such situations. While the United States and the European Union are only parties to the Protocol, China is a contracting party to both the Agreement and the Protocol. In reality, very few countries are members to the Agreement only: Algeria, Kazakhstan, Sudan, and Tajikistan[8].

Moreover, central attacks are a peculiarity of the Madrid trademark system. They do not occur in other industrial property registration systems, like the Hague Agreement (which provides for an original international registration of an industrial design, independent of any “basic” registration in an Office of origin[9]), the Patent Cooperation Treaty (which provides for an independent international registration to be filed “with a national or regional patent Office or WIPO, complying with the PCT formality requirements, in one language, and you pay one set of fees”[10]), or the Paris Convention (which provides for the filing of “separate patent applications in other Paris Convention countries within 12 months from the filing date of that first patent application.”)[11]

Procedures to carry out a central attack

A central attack against an opponent’s basic mark can be carried out through an opposition procedure before the national trademark Office where the basic mark’s application was filed, or in court proceedings if an opposition is no longer possible. The Common Regulations under the Madrid system provide guidelines as to the implementation of the Madrid Protocol: Rule 22[12] states the applicable procedure concerning the notification of the ceasing of effect of the basic application or registration. The Office of origin should notify the International Bureau of this, and whether the cancellation has affected the basic mark. The International Bureau shall promptly reflect any changes to the international registration in the International Register (disclosed in the WIPO Gazette of International Marks,[13] published on a weekly basis). The guidelines (§ 83.02) add that the “[d]ependency period is absolute, and is effective regardless of the reasons why the basic application is rejected or is withdrawn or the basic registration ceases to enjoy, in whole or in part, legal protection.”[14] The goal of the provision allowing a central attack to be carried out successfully even if court proceedings have not been concluded at the end of the dependency period, as long as they were started before its expiration, is to “[p]revent the holder of an international registration from frustrating the effects of a central attack, when his basic mark has come under attack within the five-year period of dependency, by abandoning that application or registration after the end of that period but before an Office or a court has given a final decision on the matter.”[15]

The Office of origin’s notification to the International Bureau must respect WIPO’s administrative rules. While an opposition procedure would typically take place within an appropriate tribunal, automatically making the Office aware of any invalidation of a mark, if the invalidation of the basic mark is established through court proceedings, the court often issues an order notifying the national or regional Office of any invalidation(s), in whole or in part, of the basic mark. However, neither the Protocol nor the Common rules prevents an opponent who successfully carried out the central attack from notifying the Office of origin directly, requiring them to notify the International Bureau. In fact, the guidelines expressly state the possibility of such third party to notify the Office of origin of the outcome of proceedings that affect a basic mark.[16] The Office of origin’s notification must identify the application that has been refused or opposed or the registration number that has become invalid, as well as the period within which the registration could be restored (for instance, if an appeal could be filed against the court’s decision invalidating the basic mark). The Office of origin should also include the name of the jurisdiction and the date of the decision invalidating the basic mark, but the Office need not provide a justification for the invalidation.[17] Most importantly, however, the Office of origin is to make no such notification to the International Bureau unless all avenues of appeal have been exhausted by the basic mark’s owner.[18] If made aware of any non-final proceedings that could invalidate the basic mark within the dependency period, the Office must notify the International Bureau, while clearly stating that such proceedings are not definitive and do not have final authority.[19] Such preliminary notification should be followed by a definitive notification when the decision become final. Afterwards, it is the International Bureau’s responsibility to report any changes brought to the international registration by the invalidation of the basic mark, and to notify the other Offices where the basic mark’s owner had sought protection.

Transformation of the international registration into national or regional applications

1. Transformation in the Madrid system

The transformation of an international registration following a successful central attack into national or regional trademark applications with all the Offices where the owner seeks protection will benefit from the same priority date as the former international registration.[20] However, where the international registration had designated the territory of other Madrid contracting parties subsequent to the date of the original international application, the transformation will only benefit from the same date of priority as that subsequent designation.[21] Such transformation must be done within three months of the international registration’s cancellation, and must cover the same classifications of goods and/or services as the international registration did.[22] Additionally, such transformation is available only in the case of a central attack to the basic mark or other exceptional circumstances. It is not available when the international registration is cancelled at the request of the mark’s holder.[23] The transformation can only take place in the territory of the Madrid contracting parties where the international registration had effect and was not the subject of successful invalidation proceedings.[24]

The International Bureau is not involved with transformation proceedings. It is the trademark holder’s responsibility to file national or regional applications with the Offices where he or she seeks protection. The filing of such national or regional applications is not governed by the Madrid system. Each contracting party’s Office is free to apply its own requirements to the national or regional application.[25] Some national or regional Offices might have more stringent requirements than others. For instance, the application and annual fees could be higher than with an international registration, and for jurisdictions based primarily on use in trade, proof of such use is required.

2. Transformation before the EUIPO

The European Union Intellectual Property Office (‘EUIPO’, formerly known as OHMI) has issued specific guidelines regarding the transformation (referred to as conversion) of international registrations designating the territory of the European Union “into national trade mark applications in one, more or all of the Member States.”[26] Such conversions “[c]an be requested for all or for some of the goods or services to which the act or decision invalidating the effects of an international registration for the territory of the EU relates.”[27] Furthermore, EUIPO has stated various grounds on which it can reject such conversion, for example: no transformation of an international registration into a national mark designating an EU Member State, or into an European Union trademark (‘EUTM’) within three months of the cancellation of the international registration (‘IR’) by the International Bureau would be possible if such cancellation was based on the nonuse of the trademark, or if the cancellation action originated in an EU Member State (protection will not be granted for the territory of that Member State).[28] The same is true for a conversion of an EUTM into national applications, and is subject to the same three-month time limit, starting at the date of cancellation of the EUTM. Specifically, concerning the revocation on the grounds of non-use, conversion of the IR into an EUTM will not be allowed “unless in the Member State for which conversion is requested the EUTM or IR has been put to use that would be considered genuine under the laws of that Member State.”[29] However, this factor is examined at the time of the conversion application and “no subsequent allegations by the conversion applicant regarding the substance of the case will be allowed […] if the EUTM was revoked for non-use, the conversion applicant cannot plead before the Office that it is able to prove use in a particular Member State.”[30]

Central attack: offensive and defensive strategies

1. Offensive considerations

When it comes to trademark litigation, offensive strategies range from settled co-existence of similar trademarks, to completely invalidating the totality of an opponent’s trademark portfolio. A central attack could prove very useful in the latter scenario: with one opposition or suit targeting the basic mark of the opponent on which he or she has based his or her international registration, the whole international portfolio of mark(s) could fall at once. This tactic could also be very useful in bringing a reluctant opponent to the negotiation table.

When preparing a central attack, it is essential to research the opponent’s trademark portfolio and know exactly how many registered trademarks he or she has in countries outside his or her main residence, and how many of these marks are based on an international registration. In the fashion industry, for instance, a business will often have a few dozen national trademarks from its Office of origin where the business is based, and hundreds of international marks based on the international registration of these basic marks. There is essentially no difference between invalidating a basic mark and any other mark: regardless of whether the opposition is based on an infringement action, lack of distinctiveness, or even genericide (although that would be unlikely to happen in only five years after the registration), the same arguments are used. As long as any invalidation proceedings against the basic mark are brought before the end of the five-year dependency period, their outcome will count in deciding the fate of the international registration, no matter how far in the future the court decides upon it.

If a basic mark is successfully invalidated, the winning party can request that the court notify the Office of origin where the basic mark was first filed, and remind the Office of its duty to also notify the International Bureau, after the expiration of the appeal’s period if no appeal is filed. In case the court does not issue an order of notification, the winning party can also notify the Office of origin on its own, through legal representatives. The winning party can then establish a regular channel of communication with the Office of origin and set up an alert with WIPO’s Gazette of International Marks to know exactly when WIPO will reflect the changes made to the international registration.

2. Defensive considerations

The main consideration when one suffers a central attack is damage control. The basic mark’s owner has three months from the time of the international registration’s cancellation becomes effective (published in the Gazette) to transform it into national or regional applications with the Offices where the international registration produced effects, and the owner still seeks protection, for the same goods and services as were designated for that territory in the international registration. This transformation gives rise to national or regional applications that are not governed by the Protocol or executed by the International Bureau (except for the date of priority). Of course, not using the Madrid system at all would prevent all risk of central attacks, but filing only national or regional marks in every country or region where one seeks protection could be burdensome (filing many applications vs. filing only one) and costly: the basic fee for an international registration through the Madrid Protocol is 653 Swiss francs (approximately $650), and every complementary fee for each Madrid contracting party designated is 100 Swiss francs (approximately $99). In contrast, filing national or regional applications could be quite costly: a single word mark application with the European Union Intellectual Property Office (‘EUIPO’) covering the territory of all the EU members, costs initially 900 euros (approximately $1,020) for up to three Nice classes.[31] The U.S. Trademark and Patent Office provides several options for initial application fees ranging from $250 to $400, with additional fees for requesting an extension to show use.[32] Finally, the Chinese Patent and Trademark Office requires a basic fee of $180 for up to ten Nice classes and a service fee of $319. There is an additional fee of $65 for claiming priority under a Convention.[33] Of course, there is no guarantee that these national or regional applications will not be the subject of further individual invalidation proceedings, either through oppositions or lawsuits.

Geographic considerations

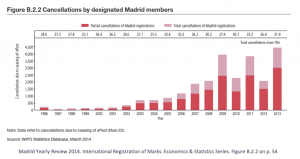

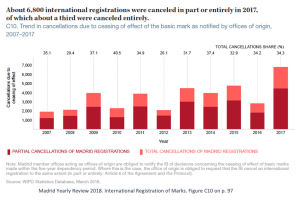

Central attacks appear to have increased substantially in recent years. Starting with fewer than 200 partial or whole cancellations due to ceasing of effect of the basic mark in 1996,[34] there were just under 7,000 such cancellations in 2017 alone.[35] In 2017, the share of total cancellations was 34.3%, compared with 65.7% of partial cancellations (for only some goods and/or services).[36]

However, cancellations can result from various causes (like a failure to pay the renewal fees on time, or a refusal to register a mark application that lacks distinctiveness, or is too similar to prior marks). Thus, these numbers of combined partial and total cancellations should not be directly attributed to central attacks. WIPO has twice researched the phenomenon of central attacks. They appear to happen rarely, and are also unequally distributed geographically. In 2004, WIPO led a first data gathering based on geographical distribution of invalidations, and by extension on central attacks, resulting in a total of 938 combined cancellations due to the ceasing of effect of a basic mark notified to WIPO by all contracting parties, and a total of 11,132 transformable designations applications filed in all the Offices of the contracting parties.[37] In 2004, there were 288 cancellations due to the ceasing of effect of a basic mark notified to WIPO from the United States (101 of those were total cancellations, and 187 were partial); only 27 of those cancellations were founded on a registered basic mark, the rest were all founded on a basic mark’s application.[38] In comparison, in 2004 the United States Office filed for 810 international registrations and received 3,147 transformable designations applications. In contrast, the Chinese Office notified only one cancellation due to the ceasing of effect of a basic mark, and received 41 transformable designations applications. In total, in 2004, all the modern-day 28 EU Member States notified 417 combined (partial and in whole) cancellations, and were the subject of 5,500 transformable designations applications.[39]

The WIPO working group gathered similar data in 2013, and requested that Offices document the occurrence of central attacks (Offices were asked to investigate how the basic mark was invalidated). From 2011 to 2012, the U.S. Office notified 525 cancellations due to the ceasing of effect, but only 16 of those appeared to have resulted from a central attack. In the same period of time, the individually participating EU Member States (with the notable exception of France and the United Kingdom) notified in total 693 cancellations due to the ceasing of effect of a basic mark, and concluded that only 189 of those appear to have been the result of an actual central attack (with a record 169 occurring in Germany!). While the European Union confirmed that out of 600 notifications of ceasing of effect, exactly 357 appeared to have resulted from central attacks. China did not provide data to the working group.[40] In the aggregate, central attacks constituted only 24.46% of all the notifications of ceasing of effect by the Offices to WIPO in 2013, and were concluded to be quite rare, with the exception of Germany and the territory of the EU, where such attacks were most frequent.[41]

Further data gathered in 2013-2014 by the International Association for the Protection of Intellectual Property (‘AIPPI’ from its acronym in French, l’Association Internationale pour la Protection de la Propriété Intellectuelle) from its working groups in several EU Member States, China, and the United States reaches the same conclusion.

The French working group’s response to AIPPI’s request featured extensive research in French case law to determine whether central attacks were occurring on a regular basis. This extensive search concluded that central attacks have rarely occurred before French courts: between 2003 to 2014, only ten decisions mention “central attack.”[42] “[T]he term ‘central attack’ is never used expressly, but what is requested from the judge is the cancellation of the international mark on the basis of Article 6(3) of the Madrid Agreement.[43]

Only two of the ten cited court cases concerning central attacks actually saw a basic mark invalidated successfully. In three of these decisions, the French courts have found that they have jurisdiction over the basic mark, but have no jurisdiction to rule on the validity of the whole international registration. They defer this authority to the International Bureau.[44] These findings show confusion on the part of French courts, since what was asked was only the invalidation of the basic mark. Despite these low numbers, “[t]he French Group nevertheless considers that it is important to highlight the utility of the central attack for the purposes of amicable settlement of disputes, because this concept is frequently used in pre-litigation procedures in order to request consequences outside of France.”[45] Similarly, the Japanese group also provided data concerning central attacks on its territory: “[b]etween 2004 and 2013, the number of basic registrations and applications reported as terminated from the Japanese Patent Office to WIPO’s International Bureau is 1248 total, out of which in 16 cases a central attack was used.”[46] The Japanese group pointed out that a central attack is typically not the main cause of a basic mark’s invalidation: “there are more cases of termination due to ‘self-destruction’ (termination without being attacked, which appears to be caused mostly by rejection in relation to other prior trademarks).[47]” Furthermore, the group added that “[a]ccording to proprietors of well-known or famous marks, when someone maliciously registers a well known mark by designating several countries through the international registration system ahead of its owner, a central attack will be more efficient than invalidation actions filed against this person in the relevant countries.”[48]

In comparison, the German group did not provide any data, and only noted that,

“[T]he German Patent and Trademark Office or a German Court will base its decision concerning the central attack solely on Article 6(2) and (3) of the Madrid Agreement as well as in Article 6(2) and (3) of the Protocol, but not additionally consider arguments like the rationale effect or the effectiveness of a central attack which have a more legislative content”[49].

Likewise, neither the British, American, nor Chinese AIPPI working groups provided any data on the occurrence of central attacks on their territory, and only noted that the mere threat of one is a good negotiating tool in trademark disputes involving large portfolios of international marks. The Chinese group did, however, note that because of its centralized system and efficiency, the Madrid system is often the first choice when it comes to filing trademarks internationally from China.[50]

Finally, the American group noted that the Madrid system was not widely used by U.S. applicants, and the question of central attacks is this irrelevant to the U.S.: “[m]ost U.S. trademark owners are unfamiliar with how Madrid works and are skeptical of its usefulness. It is promoted on the basis of efficiency and cost savings but practitioners see only a reallocation of expenses, and the interposition of another party in the chain of communication”. The American AIPPI group also highlighted the challenges the U.S. system throws at the applicant including, a suggestion for a narrow claim and use of trademarks, higher likelihood of opposition, and a larger registry of conflicting marks:

He or she should claim relatively narrow specifications of goods and for each a bona fide intention to use the trademark on these goods in the U.S.; and the trademark must be used on all of the claimed goods before the U.S. registration will issue. Moreover, the U.S. has a relatively high opposition rate, has strict examination procedures on both absolute and relative grounds, and a large register of potentially conflicting trademarks. Many U.S. applicants prefer to file directly in other countries to take advantage of broader specifications of goods.[51]

WIPO legislative developments

The 8th session of WIPO’s working group (2010) on the legal development of the Madrid system addressed the broad question of how to eliminate the requirement for a basic application or registration in the Madrid system. The group examined a proposed mechanism that would allow for a “central attack, by way of opposition to the international registration, before opposition boards established at WIPO.”[52] An alternative to a central attack was also suggested, notably providing a “list of cancellation grounds to identify situations which would be likely to lead to refusal of the international registration in all designated Contracting Parties and to prevent abusive international filings”[53] by WIPO. Examples of such cancellation grounds include similarity of a mark in an international application to a senior internationally registered mark, or the presence of a generic or descriptive mark in an international application.

In conclusion, it is likely that the Madrid system will remain as is, and will not eliminate the threat of central attacks because of the balance of interests it provides for third parties, and the efficient elimination of invalid marks at the international level. With this in mind, practitioners who use the Madrid system should be prepared to lead both offensive and defensive trademark strategies around the threat of central attacks. While awaiting new and more conclusive data from WIPO, it is important to remember that successful central attacks are rare, and almost exclusively affect EU countries.

[1] Some law firms and trademark practitioners rang alarm bells about the threat of central attacks when their countries joined the Madrid Protocol: for instance, Bird & Bird LLP https://www.twobirds.com/en/news/articles/2004/madrid-protocol-and-community-tm

[2] In order to invalidate the international registration and its subsequent registrations in contracting parties to the Madrid system

[3] Article 6 of the Madrid Agreement

[4] WIPO Guide to the international registration of marks § 83.02 defines a central attack as: “The process by which an international registration may be defeated for all countries in which it is protected, by means of a single invalidation or revocation action against the basic registration has become generally known by the term “‘central attack’.”

[5] Article 9quinquies of the Protocol

[6] Article 6 of the Protocol

[7] Article 99sexies of the Protocol

[8] WIPO. List of Contracting Parties to the Madrid Agreement or the Madrid Protocol in the alphabetical order of the corresponding ST.3 codes http://www.wipo.int/madrid/en/madridgazette/remarks/2009/50/gaz_st3.htm

[9] WIPO. The Hague System for the International Registration of Industrial Designs. Main Features and Advantages. “No prior national or regional application or registration is required.” p. 5 http://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/designs/911/wipo_pub_911.pdf

[10] WIPO Protecting your Inventions Abroad: Frequently Asked Questions About the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) http://www.wipo.int/pct/en/faqs/faqs.html

[11] WIPO Protecting your Inventions Abroad: Frequently Asked Questions About the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) http://www.wipo.int/pct/en/faqs/faqs.html

[12] Rule 22 on the Ceasing of Effect of the Basic Application (as in force on April 1st, 2016)

[13] “The WIPO Gazette of International Marks is the official publication of the Madrid System. WIPO http://www.wipo.int/madrid/en/madridgazette/

[14] WIPO Guide to the international registration of marks B.II.94 § 83.02

[15] WIPO Guide to the international registration of marks B.II.95 § 84.03

[16] WIPO Guide to the international registration of marks B.II.98 § 85.07

[17] WIPO Guide to the international registration of marks B.II.96-97 § 85.02

[18] WIPO Guide to the international registration of marks B.II.97 § 85.05

[19] WIPO Guide to the international registration of marks B.II.97-98 § 85.06

[20] WIPO Guide to the international registration of marks B.II.94 § 83.04

[21] WIPO Guide to the international registration of marks B.II.100 § 88.01

[22] WIPO Guide to the international registration of marks B.II.101 § 88.04

[23] WIPO Guide to the international registration of marks B.II.100 § 88.02

[24] WIPO Guide to the international registration of marks B.II.100 § 88.03

[25] WIPO Guide to the international registration of marks B.II.101 § 88.06

[26] EUIPO Guidelines for examination of European Union trade marks. Part E: Register Operations. Section 2: Conversion. 2.2. Conversion of IRs designating the EU (October 1st, 2017) p. 4 https://euipo.europa.eu/tunnel-web/secure/webdav/guest/document_library/contentPdfs/law_and_practice/trade_marks_practice_manual/WP_2_2017/Part-E/02-part_e_register_operations_section_2_conversion/part_e_register_operations_section_2_conversion_en.pdf

[27] EUIPO Guidelines for examination of European Union trade marks. Part E: Register Operations. Section 2: Conversion. 2.2. Conversion of IRs designating the EU (October 1st, 2017) p. 4 https://euipo.europa.eu/tunnel-web/secure/webdav/guest/document_library/contentPdfs/law_and_practice/trade_marks_practice_manual/WP_2_2017/Part-E/02-part_e_register_operations_section_2_conversion/part_e_register_operations_section_2_conversion_en.pdf

[28] EUIPO Guidelines for examination of European Union trade marks. Part E: Register Operations. Section 4: Grounds Precluding Conversion. (October 1st, 2017) p. 6 https://euipo.europa.eu/tunnel-web/secure/webdav/guest/document_library/contentPdfs/law_and_practice/trade_marks_practice_manual/WP_2_2017/Part-E/02-part_e_register_operations_section_2_conversion/part_e_register_operations_section_2_conversion_en.pdf

[29] EUIPO Guidelines for examination of European Union trade marks. Part E: Register Operations. Section 2: Conversion. 4.1 Revocation on the grounds of non-use (October 1st, 2017) p. 4 https://euipo.europa.eu/tunnel-web/secure/webdav/guest/document_library/contentPdfs/law_and_practice/trade_marks_practice_manual/WP_2_2017/Part-E/02-part_e_register_operations_section_2_conversion/part_e_register_operations_section_2_conversion_en.pdf

[30] EUIPO Guidelines for examination of European Union trade marks. Part E: Register Operations. Section 2: Conversion. 4.1 Revocation on the grounds of non-use (October 1st, 2017) p. 4 https://euipo.europa.eu/tunnel-web/secure/webdav/guest/document_library/contentPdfs/law_and_practice/trade_marks_practice_manual/WP_2_2017/Part-E/02-part_e_register_operations_section_2_conversion/part_e_register_operations_section_2_conversion_en.pdf

[31] EUIPO. Fees https://euipo.europa.eu/ohimportal/en/eu-trade-mark-regulation-fees

[32] USPTO. Trademark fee information https://www.uspto.gov/trademark/trademark-fee-information

[33] China Trademark Office. Schedule of fees for Chinese trademark https://www.chinatrademarkoffice.com/index.php/about/fee

[34] Madrid Yearly Review 2014. International Registration of Marks. Economics & Statistics Series. “Figure B.2.2 Cancellations by designated Madrid members”. Note: Data refer to cancellations due to ceasing of effect (Rule 22). Source: WIPO Statistics Database, March 2014 p. 54 http://www.wipo.int/publications/en/details.jsp?id=3197&plang=EN

[35] Madrid Yearly Review 2018. International Registration of Marks. Section C: Statistics on Administration, Revenue and Fees. “Figure C10 Trend in cancellations due to ceasing of effect of the basic mark as notified by offices of origin, 2007–2017”. WIPO, 2018 p. 97 https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo_pub_940_2018.pdf

[36] Madrid Yearly Review 2018. International Registration of Marks. Section C: Statistics on Administration, Revenue and Fees. “Figure C10. Trend in cancellations due to ceasing of effect of the basic mark as notified by offices of origin, 2007–2017” WIPO, 2018 p. 97 https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo_pub_940_2018.pdf

[37] WIPO Working Group on the Legal Development of the Madrid System for the International Registration of Marks. Eight Session. MM/LD/WG/8/4. June 17, 2010 http://www.wipo.int/meetings/en/details.jsp?meeting_id=17463

[38] WIPO Working Group on the Legal Development of the Madrid System for the International Registration of Marks. Eight Session. MM/LD/WG/8/4. June 17, 2010 http://www.wipo.int/meetings/en/details.jsp?meeting_id=17463

[39] WIPO Working Group on the Legal Development of the Madrid System for the International Registration of Marks. Eight Session. MM/LD/WG/8/4. June 17, 2010 http://www.wipo.int/meetings/en/details.jsp?meeting_id=17463

[40] WIPO Working Group on the Legal Development of the Madrid System for the International Registration of Marks. Eleventh Session. MM/LD/WG/11/4. August 22, 2013. http://www.wipo.int/meetings/en/details.jsp?meeting_id=29762

[41] WIPO Working Group on the Legal Development of the Madrid System for the International Registration of Marks. Eleventh Session. MM/LD/WG/11/4. August 22, 2013. http://www.wipo.int/meetings/en/details.jsp?meeting_id=29762

[42] AIPPI Question Q239. French Group. April 28, 2014 https://aippi.org/library/q239-group-reports-fr/

[43] AIPPI Question Q239. French Group. April 28, 2014 https://aippi.org/library/q239-group-reports-fr/

[44] AIPPI Question Q239. French Group. April 28, 2014 https://aippi.org/library/q239-group-reports-fr/

[45] AIPPI Question Q239. French Group. April 28, 2014 https://aippi.org/library/q239-group-reports-fr/

[46] AIPPI Question Q239. Japanese Group. May 21, 2014 https://aippi.org/library/q239-group-reports-jp/

[47] AIPPI Question Q239. Japanese Group. May 21, 2014 https://aippi.org/library/q239-group-reports-jp/

[48] AIPPI Question Q239. Japanese Group. May 21, 2014 https://aippi.org/library/q239-group-reports-jp/

[49] AIPPI Question Q239. German Group. May 19, 2014 http://aippi.org/library/q239-group-reports-de/

[50] AIPPI Question Q239. Chinese Group. April 21, 2014 https://aippi.org/library/q239-group-reports-cn/

[51] AIPPI Question Q239. United States of America Group. May 21, 2014 https://aippi.org/library/q239-group-reports-us/

[52] WIPO Working Group on the Legal Development of the Madrid System for the International Registration of Marks. Eight Session. MM/LD/WG/8/4. June 17, 2010 http://www.wipo.int/meetings/en/details.jsp?meeting_id=17463

[53] WIPO Working Group on the Legal Development of the Madrid System for the International Registration of Marks. Eight Session. MM/LD/WG/8/4. June 17, 2010 http://www.wipo.int/meetings/en/details.jsp?meeting_id=17463