A recent conference at Stanford Law brought together top-flight litigators, intellectual property scholars, representatives from USPTO and WIPO, and in-house counsel for a rousing discussion of emerging issues in design patents.

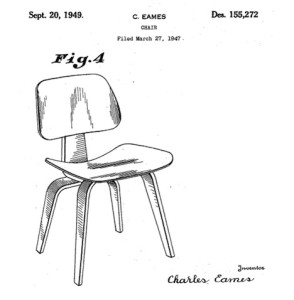

In contrast to an ordinary utility patent, a design patent is granted to an inventor of a new, original and ornamental design for an article of manufacture, and lasts for 14 years from the date of issuance. 35 U.S.C. 171, 173. A design patent contains only a single claim, and photographs or drawings that follow certain drafting conventions and applicable PTO rules. 37 CFR 1.84, 37 CFR 1.152.

Recent cases affirm the “ordinary observer” standard — but application in context of prior art is inconsistent

Design patents began to get increasing attention in 2008, when the Federal Circuit issued a game-changing decision in Egyptian Goddess v. Swisa, 435 F.3d 665 (Fed. Cir. 2008), holding that the “ordinary observer” test is the sole test for design patent infringement. The court looked back to the standard first stated in Gorham Mfg. Co. v. White, 81 U.S. 511 (1871), but clarified that the test is to be conducted in the context of the prior art. The ruling did away with the “point of novelty” test, freed district courts from issuing detailed verbal descriptions of the design claims if verbal elaboration would not be helpful, and placed the burden of production of prior art for any affirmative defenses on the accused infringer. This has made it much easier to prove design patent infringement, and consequently made design patents much more valuable, as Paris Hilton discovered in starting her own shoe line. Experts now strongly recommend that inventors obtain design patent protection for any product with novel and unique visual appearance.

In litigation over the popular clog shoes, Int’l Seaway Trading Corp. v. Walgreens Corp., 589 F.3d 1233 (Fed. Cir. 2009), the Federal Circuit affirmed that the “ordinary observer” standard also applies to anticipation and obviousness analyses. The court held that designs must be compared in their entirety, ignoring minor or trivial differences; however, significant differences need not be limited to the exterior view alone, and may be seen in other views, such as the insoles of the shoe. The court further clarified that the only role for the perspective of one skilled in the art (or the “ordinary designer”) is in determining whether to combine earlier references to arrive at a single piece of prior art for obviousness comparison.

Conference panelists debated whether recent court decisions have been inconsistent in considering prior art in infringement analysis. Some recent opinions have relied on an initial assessments of whether the designs are “sufficiently distinct” or “plainly dissimilar” in determining whether prior art should be consulted at all. CompareMinka Lighting, Inc. v. Maxim Lighting Int’l, Inc. (N.D. Tex. Mar. 16, 2009) withFanimation, Inc. v. Dan’s Fan City, Inc., 2010, (S.D. Ind. Dec. 16, 2010) aff’d, 444 F. App’x 449 (Fed. Cir. 2011); see also Revision Military, Inc. v. Balboa Mfg. Co., 700 F.3d 524 (Fed. Cir. 2012). Panelists discussed research in psychology of shape perception, which suggests that the human visual system is attuned to spot differences, and that judgements about difference are greatly affected by the context and manner of presentation—and the implications of these findings for jury and bench trials. An Ohio court will soon have the opportunity to weigh in on the role of prior art in infringement analysis of cupcake batter separators in Kimber Cakeware v. Bradshaw Int’l (S.D. Ohio 2013).

Functionality doctrine, graphical user interfaces, and relationship to trade dress protection will require further clarification

Because design patents are granted for ornamental designs only, functional elements of the design are not subject to protection. For example, in Richardson v. Stanley Works, Inc., 597 F.3d 1288 (Fed. Cir. 2010), Federal Circuit upheld a finding of no infringement when the district court properly factored out functional elements of a multi-use tool, including the handle, hammerhead, jaw, and crowbar. Questions of functionality become more nuanced, however, when considering ergonomic and usability design requirements. Panelists and attendees debated what weight courts should assign to requirements dictated by engineering analysis, which may limit dimensions and angles in a product, as well as production requirements that may rule out certain design alternatives.

The functionality debate gathered steam in a discussion of recent Apple v. Samsungdesign patent litigation and the developing area of protection for graphical user interfaces. An argument could be made that certain aspects of icons are dictated by function – such as bright colors for visibility, image that signifies the app, and a shape that comfortably fits an average fingertip. The exclusion of certain elements, however, creates a tension with the often-stated maxim that the design must be considered in its entirety (reiterated in Int’l Seaway), and some attendees argued that a close focus on functionality may invalidate legitimate design innovations.

This debate led to a greater discussion of the goals of design protection, and whether another system, such as a registry, may be better suited to meet the needs of designers. Under the current system, the 14-year protection granted by a design patent could potentially be used by the owner to establish secondary meaning for the purpose of trade dress protection, which is unlimited in time. Panelists debated whether the Supreme Court’s holding in Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros., Inc., 529 U.S. 205 (2000), that product design is entitled to protection as unregistered trade dress when it has acquired secondary meaning was predicated on an understanding that a design cannot qualify for both trade dress and design patent protection. Comparative empirical research is needed to shed light on the benefits of different design protection regimes in use throughout the world. Nonetheless, the value of aesthetically pleasing products that bring an element of art into our everyday tasks is likely to continue to be recognized by the public.

WIPO, USPTO and in-house representatives discuss new application procedures and need for knowledgeable practitioners

The Patent Law Treaties Implementation Act of 2012, signed by President Obama, implemented both the Geneva Act of the Hague Agreement Concerning the International Registration of Industrial Designs and the Patent Law Treaty. A representative of WIPO, Mr. Alan Datri, described the new international application process. Under the Hague Agreement, separate industrial design patent filings will no longer be required for each jurisdiction. Instead, a single English-language application can be filed directly with the World Intellectual Property Organization or indirectly with the USPTO, and can lead to protection in multiple designated member countries, including the European Union. The new process is expected to result in cost savings and to protect small and medium sized businesses that lack a global footprint by enabling them to easily acquire design protection in multiple markets. Asian countries are expected to join the agreement in the coming years.

The USPTO has recognized the increasing importance of industrial design in the global marketplace, noting that good design makes products “intuitive, aesthetically appealing, and comfortable to handle.” Mr. Brian Hanlon of the USPTO discussed the changes to design patents under the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (AIA). Because design patents are not published, they will not be affected by third-party pre-issuance submissions, nor will design patents qualify for priority examination. However, design patents qualify for a “Rocket Docket” expedited examination under35 CFR 1.155. Mr. Hanlon discussed new fees, which include a substatial discount offered to micro-entities intended to stimulate innovation. Mr. Hanlon also stressed the importance of following the new application data sheet guidelines.

Ms. Katie Maksym, design patent counsel for Nike, which is among the top 5 design patent holders, discussed the fast pace of the industry. She emphasized the importance of the expedited application under the Rocket Docket in her practice, where an issuance may be obtained in as little as 3 months and a notice of allowance in just a few weeks. Design patents constitute a significant part of Nike’s intellectual property portfolio, which Ms. Maksym estimated to contain about 10,000 design patents, compared to 3,000-4,000 utility patents. Ms. Maksym stressed the role of experts who are closely familiar with the meticulous drawing and applications requirements, and who have studied which design patent issues have been litigated and what can be gleaned from USPTO’s rejections.

A recent illustration of meticulousness needed in the application process can be seen in In re Owens, 710 F.3d 1362 (Fed. Cir. 2013) which addressed the written description requirement in the context of priority under § 120 for design patents, finding that that a new design region on a water bottle would not receive the benefit of the priority date because it was not adequately indicated to be in the inventor’s possession as of the original application. Panelists agreed that a knowledgeable practitioner is necessary to navigate the application process but delivers results in terms of costs savings and timely protection of valuable designs in the marketplace.